By Chris Schulz

Investigative Journalist | Kaipūrongo Whakatewhatewha

Used clothing is filling up landfill in record amounts, contributing to carbon emissions and impacting the environment. Some recyclers have found a better option for old clothing – but they desperately need more support.

In a garage in New Lynn, Tāmaki Makaurau, Lucy-Mae Goffe-Robertson has pulled out her needle and thread. Sitting on a couch surrounded by handmade cushions, she's busy stitching together a giant flag for a recent order. But there’s a problem: "I didn't realise I’d made it upside down," she says. “I’m going to cut it up and redo it the right way.”

The flag, cushions and everything else made in this homely space have been created using old, donated clothes, and textile ‘waste’ that would have otherwise gone to landfill. Dubbed Fashion Rebellion Aotearoa, it’s here that Goffe-Robertson has built a collective protesting against the waste created by the fast fashion industry. “I had this massive garage,” she says, explaining her project’s humble beginnings 5 years ago. “I thought, ‘What more can I do?’”

Along with 22 like-minded souls, she’s attempting to spark a revolution. Together, they have held protests, including a fashion show using entirely upcycled, recycled and repurposed clothing. They help educate people about what to do with their used clothes. They turn old clothes into new products, shredding them by hand and stuffing them into cushions, poufs and bolsters. These are branded as “soulcycled” items and sold in local stores.

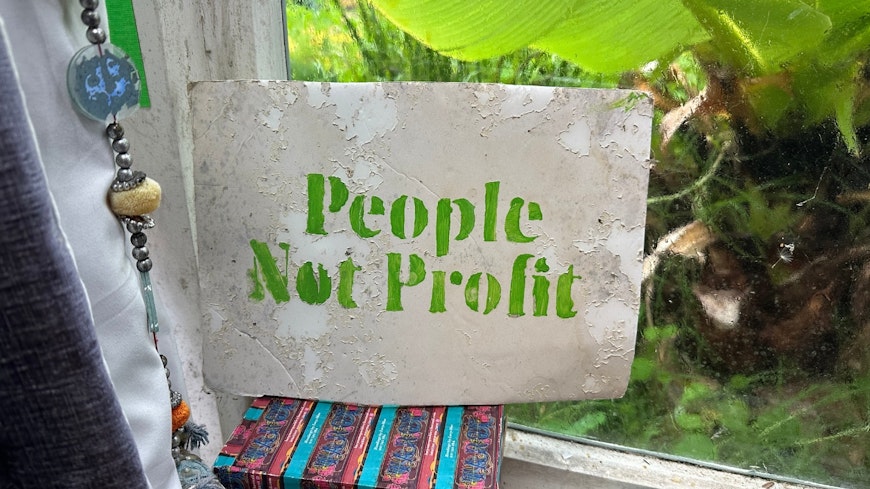

They’ve taken their protest further, printing slogans onto protest flags and posters and unfurling them at events, and making patches people can sew or pin onto their own clothes themselves to show support for the cause. “People Not Profit” reads one; “Fuck Fast Fashion,” says another. In conjunction with Greenpeace, they’ve launched a petition that calls on the Government to introduce measures to “slow down the production and consumption of fast fashion in New Zealand” and to “require producers to cover the costs of the pollution caused by their products over their lifecycle”.

Goffe-Robertson says we need her collective because of the fashion industry. Fast fashion – that’s cheap, mass-produced clothing designed to be worn a few times then discarded – is clogging up landfill in record amounts. Textile waste, including bedding and fashion industry by-products, as well as synthetic clothing, is being thrown out like never before. One estimate suggests 350 kilograms is sent to landfill every minute in Aotearoa alone, creating carbon emissions and other environmental issues.

She understands the need for new clothes. “We want to feel new,” she says. “Clothes are our identity, our persona. It’s tied up in our emotions.” The problem is fast fashion, which has created an insatiable consumer appetite for new clothing, resulting in an unsustainable clothing industry. “It’s the sheer amount of clothes. It’s overproduction; it’s capitalism; it’s profit; it’s all more, more, more. It’s relentless,” Goff-Robertson says. “This is a rebellion.”

How did we get here?

On a recent visit to the online shopping giant Temu, I searched for an outfit I could wear to an upcoming vegetable-themed costume party. For just $19.83, I could purchase a T-shirt and matching shorts covered in sweet-corn kernels. If I wanted to, I could pair this with a ‘hand’-crocheted corn-head mask for $22.82 and watermelon sneakers for $21.30. Then, I could swap out the shorts with a pair of angry banana-print pants for $16.23.

With the promise of free shipping, that full outfit would cost me less than $100 – and would likely only be worn once. That, says University of Auckland marketing professor Dr Michael Lee, is the problem with fast fashion. “It’s a social norm that you need to look a certain way,” he says. “Fast fashion feeds into this. The entire economic system is designed to ratchet up, rather than down.”

Dr Lee has explored the social and psychological behaviours that have led to the increasing speed of fashion cycles. Add in a cost-of-living crisis that is stretching everyone's budgets and online shopping giants Temu and SHEIN encouraging mass consumerism and we have a perfect storm. “Back in the old days, clothing styles were determined by changes in the weather,” Lee says. “Fast fashion changes every few months, so you've got a quadrupling of the amount of new options we're being exposed to.”

According to a report by Yale Climate Connections, the online shopping giant SHEIN is estimated to add 10,000 new clothing products to its site every single day. The repercussions are well documented in landfills around the country. Greenpeace estimates 180,000 tonnes of textile waste are discarded in Aotearoa landfills annually. A report from The Earth Call suggest 6-8% of global gashouse emissions are caused by the textile industry. Add in the harm the creation of cheap clothing could be doing in its country of origin, the addition of dyes and synthetics in clothing (that’s plastic, which takes much longer to break down than cotton or wool), and it’s easy to feel overwhelmed.

Lee points to the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh to show how bleak the fast fashion industry has become. Back then, a structurally unsafe building housed workers in poor conditions to create clothes for some of the world’s biggest brands. When the building collapsed, 1,134 people died, and 2,500 were injured. In the aftermath, many major fashion companies were criticised for manufacturing their garments there.

But Lee says little has changed since – and things may have even got worse. “They’re willing to work crazy hours in really difficult conditions to pump out stuff you might wear once and then chuck away,” he says. “It’s very difficult and kind of depressing.”

A stitch in time

Inside the front doors of a large Penrose warehouse in an industrial part of South Auckland, a huge pile of tatty clothes greets visitors. This, says Jeff Vollebregt, represents how much textile waste is thrown into Aotearoa landfills every minute of every day. “It’s actually 3.5 tonnes every 10 minutes,” says Vollebregt, “but we couldn’t fit 3.5 tonnes of clothing in that space.”

ImpacTex is his answer to this staggering problem. Coming from a corporate background, Vollebregt pivoted to textile waste solutions after a nagging concern grew too big to ignore. For years, Vollebregt had seen the waste generated by major garment manufacturers only getting worse as fast fashion demands increased. “Nothing was being done in New Zealand,” he says. “We thought, ‘There’s an opportunity to make a difference.’”

Initially, Vollebregt and his wife Carol set up shop in a smaller facility down the road. They soon encountered problems: the scale of textile waste was overwhelming. Like Goffe-Robertson, they cut up clothes by hand, shredded them and turned them into cushion stuffing. “But how much cushion filler do people want?” he says. “We were thinking, ‘We have to do more, there’s got to be more that we can create.’”

The result of several years of research and development is Vollebregt’s recycling partnerships. ImpacTex’s recovered textile waste is being turned into all kinds of things, from protective packaging for wine bottles to table mats, bench tops, indoor and outdoor signage, insulation and noise reduction panels for offices. The item he’s most proud of is a retail poster made from recycled denim that can be recycled and reprinted again and again. “This,” says Vollebregt, showing off a carry bag made of textile waste, “is an untouched world, a new market.”

Companies that have used clothing or uniforms they don’t want to send to landfill can arrange to deliver the waste to ImpacTex instead. For consumer waste, AS Colour, Icebreaker, Kathmandu, Westfield Newmarket and Macpac have ImpacTex collection bins in many stores. Anyone can drop almost any type of used clothing into them. Vollebregt aims to stop as much clothing as possible from going to landfill. “If we’re taking it, that’s great,” he says. “I’d be crying if it stopped [coming in].”

When it does come in, his team of five full-time staff sort through it all. The best clothes are cherry-picked, repaired and sent to families in need. Carol, ImpacTex’s business manager, shows me a perfectly good hoodie and pair of shorts that recently arrived. “They could have gone to landfill,” she says, “but these are destined for one of our amazing Charity partners”. ImpacTex has donated well over 60,000 garments and homewares in the short time they’ve been operating.

ImpacTex can find a use for almost any item of used clothing – except underwear and socks. Loose zips remain another unsolved piece of the puzzle. “We’re constantly looking for solutions,” says Vollebregt. If he feels like a pioneer, that’s because Vollebregt kind of is. But it’s not easy. “There’s plenty here to do, and there’s more coming in all the time,” says Vollebregt.

Carol says, sometimes, workwear can come in contaminated – covered in mud, or worse. To get through it all, they’ve found a way to celebrate small wins. When an ImpacTex staff member finishes sorting a full pallet of clothing, a stereo emerges, pop tunes are blasted and everyone comes down to have a boogie. “I make everyone come down,” Carol says.

What needs to change?

Vollebregt's 5-year plan is to keep ImpacTex in its current location but use the skills the team has developed to increase the amount of textile waste the company can process. To do that, several things would help: regulatory support that includes extending the responsibility for clothing brands to incorporate end-of-life plans with their products; subsidies for recycling companies like his that are offering circularity solutions and education campaigns that raise awareness for textile recycling options that are different to sending used garments to the dump.

Lee, from the University of Auckland, agrees regulation would help. “The trick is to do it in a way that doesn't allow corporations to pick and choose the best regulations for them,” he says. If restrictions were placed on fashion companies here, those companies could easily move to another country that has less stringent regulations, he says. “If all Western nations said, ‘From now on, we’ll force you to offer lifetime warranties and handle your waste, they could just go, ‘Well, that sounds like it’s going to cost us a lot’, and they’d just go manufacture in Africa or Bangladesh.”

In her New Lynn garage, Goffe-Robertson believes people want to do the right thing with their old clothes, but there’s still just far too much of it for her to deal with it all. “I can’t be bothered educating everyone,” she says. “I don’t have the energy.” Recently, she removed the address for Fashion Rebellion from her social media pages. “I was getting bags of stuff just thrown on the lawn,” she says.

The only solution to this, she says, is to pressure the government to create laws that “hold fast fashion corporations to account for the waste that they’re creating”. There is only so much consumers – or recyclers like her – can do. “Make them pay for the waste or tax for the waste,” she says. Goffe-Robertson suggests another bold measure: “Restrict the amount of clothes that can be sold in the first place … just stop making clothes,” she says. “We have too many clothes.”

How to reduce your textile waste

Consider purchasing clothes that will last longer. Clothes made of natural material like cotton or wool can be more expensive, but they last much longer. They can also break down faster in recycling facilities.

Learn how to repair or repurpose your old clothes.

Buy second hand, swap clothes with friends or neighbours, or, failing that, sell them through a fashion upcycler and claim credits.

Dispose of your textile waste correctly. Impactex bins are placed in many AS Colour stores, as well as Icebreaker, Kathmandu, Westfield Newmarket and Macpac. Some clothing brands will take back their old clothes.