By James le Page

Former Product Test Team Leader | Kaiārahi Kapa Whakamātau Hautaonga

Manufacturers of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) claim some very low numbers when it comes to fuel use. Sometimes, it seems too good to be true.

So, with the support of Te Manatū Waka – Ministry of Transport, we assessed the fuel use of five PHEVs and five hybrids from five brands to see how real-world fuel consumption compares with the manufacturers’ claims. While it’s a small sample, it has generated some useful insights.

Manufacturers’ fuel efficiency figures come from laboratory tests conducted under controlled settings. This method is used to calculate all fuel efficiency claims you see. However, when you drive a vehicle on real roads, the fuel efficiency is likely to be lower – and lower still if you don’t drive with efficiency in mind.

In New Zealand, the Clean Car Discount Scheme uses the published fuel use to calculate fees and rebates for each car. A healthy proportion of hybrids and PHEVs are in line to receive rebates, so it’s important that the stated fuel use isn’t exaggerated. Having the fees and rebates set to the right level is crucial for encouraging people into the right sort of vehicles.

The background – claims under the spotlight

Fuel efficiency claims made for hybrids and PHEVs have come under the spotlight overseas. In 2020, Europe’s leading clean transport campaign group, Transport & Environment, presented a briefing paper of the real-world CO2 emission performance of 20,000 PHEVs in Europe. It found that their emissions (and fuel use) are, on average, “over two and a half times those of official test values”.

In the same month, the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) released a white paper that found: “PHEV fuel consumption and tailpipe CO2 emissions in real-world driving, on average, are approximately two to four times higher than type-approval values.”

We also tested the real-world fuel efficiency of hybrids, PHEVs and electric vehicles (EVs) in 2020. We uncovered that the price of running a Hyundai Ioniq PHEV for a week compared very similarly to the hybrid version. It was a surprising result – we expected the PHEV cost to be much lower.

Explaining hybrids and PHEVs

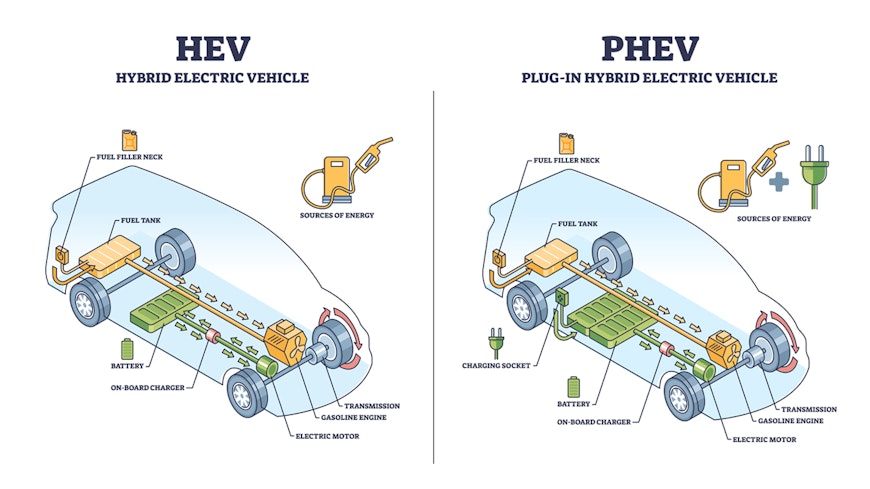

Hybrids have a small electric motor and battery that is recharged by the petrol engine, and when slowing down by regenerative braking. The electric motor is powerful enough to drive the car at low speeds, but generally it’ll run out of juice when you approach 30-50km/h. You don’t need to plug them in, and they work just like any other car you’ve driven.

The PHEV is the next step up. The electric motor and batteries are bigger; the largest batteries we saw were in the RAV4 PHEV, which claimed an all-electric range of 93km on the dashboard. The batteries can be recharged on the fly by the petrol motor and regenerative braking, but the bulk of charging is done by plugging it into the electricity network at home each day.

The real-world test

Each vehicle we trial gets the same treatment: a week of commuting in rush hour from Lower Hutt to Consumer HQ (a round trip of 28km); a run to the supermarket; and a drive over the Remutaka Hill and back to see how it goes on a longer weekend trip. In total, one week’s usage makes for about 270km of motoring.

We record fuel use (both actual and on the trip computer) and measure electricity usage where appropriate, with PHEVs. The actual fuel use is measured by filling the tank to the brim at the start of the trial and then again at the end, and comparing numbers. It’s an inexact science that doesn’t use any specialist or calibrated equipment, but it’s still a repeatable, real-world appraisal.

We also updated the figures for the Hyundai Ioniq Hybrid and PHEV we tested in 2020 to make them comparable (petrol was $1.97 back then). The other vehicles involved in the trial were:

All vehicles were loaned to us by the car companies.

Note: We asked Mitsubishi NZ to take part as it sells the very popular Outlander and Eclipse Cross PHEVs. Communication dried up with the brand, so we pivoted away to other manufacturers.

Results

Hybrid cars

Plug-in hybrid cars (PHEVs)

Measured power usage on PHEVs

Actual fuel and electricity costs

The cars represent a good mix of small hatches right up to a big SUV, in the Toyota Highlander. The hybrids all delivered fuel economy between 4.0 and 6.6L/100km, while the PHEVs were between 1.3 and 3.1L/100km.

While none of them exactly met their claimed fuel efficiencies on our test, the hybrids were closer in terms of percentage shifts.

Drawing some conclusions

It all boils down to this.

PHEVs averaged 45% over their claimed fuel use on their trip computers and 73% over with the fuel measured at the pump.

Hybrids averaged 10% over their claimed fuel use on their trip computers and 20% over with the fuel measured at the pump.

Percentage difference from claimed fuel usage

It’s important not to sensationalise those figures – it’s not robust science. Rather, it’s real-world driving with the percent gains blown out by the small numbers in the PHEV claims. Even so, it is quite telling in our sample that the figures were much higher than claimed.

Still, PHEVs don’t use much fuel compared with hybrids. Despite effectively costing the same per 100km, the largeish-SUV MG HS Plus EV (a PHEV) used less fuel than the small Toyota Yaris ZR (a hybrid).

Our results aren’t as stark as the European studies, but it’s still a big chunk over the claimed amount for PHEVs. One reason might be because those studies found that people weren’t charging up the vehicles as often as anticipated while we did it each night (as you really should).

We’re not a painting a picture to say that PHEVs are rubbish; it’s just that things come unstuck as soon as you go on longer trips. All the PHEVs spent the majority of their time in EV mode until we hit the highway on the weekend and drained the battery. So, if you only ever drive around within your EV-only range, you’ll easily go below the claims.

The key takeaway for consumers is this: If you’re in the market for a vehicle, only buy a PHEV if a lot of your driving covers shorter distances that will use the EV-only mode, and you are able to recharge the battery at home. If most of your trips are longer, you might be better off saving on the purchase costs and opting for a cheaper hybrid instead.

Lessons from the experience

Driving car after car and switching between PHEVs and hybrids gave us insights into how they fit into everyday life.

Hybrids and PHEVs are better than regular petrol cars when coming out of low-speed corners and going uphill, because the little electric motor picks up the slack and keeps the momentum going.

Bumper-to-bumper driving suits mild hybrids just fine, and that’s when they return the best figures. This is because they spend more time in EV mode when slowly crawling along and coasting to a stop. Even the big Toyota Highlander returned figures of 3.9L/100km (against a claimed 6.2L/100km) when driving to work on a particularly slow morning.

The latest PHEVs are generally very good and have enough power keep the car driving at highway speeds while running the air con on full, without needing the petrol motor as backup. They still might kick back into hybrid mode when you encounter steep hills in 100km/h zones or floor it when overtaking.

Treat the predicted range of EV-only driving for PHEVs as a stab in the dark. The range you will achieve all comes down to the sort of driving you’ll do in your unique situation. The only way you’ll know is when you try it for yourself. The only PHEV that met its claimed range was the Kia Niro (63km on the dashboard when fully charged). The others fell short.

Highway speeds and steep hills drain the PHEV battery very quickly when compared with slower, rush-hour driving.

Make sure you actively manage your PHEV. Usually, you can change the drive modes. Put it into EV mode – that way it’ll be reluctant to jump out of EV driving and start using petrol if you prod the accelerator too hard.

If you pick the right PHEV and only commute or drive within your achievable EV range, you’ll hardly ever use petrol. Ever. The only time you will is when you go for longer road trips.

A PHEV tends to sacrifice the spare wheel and often a bit of boot space compared with the hybrid version. That’s because that space is needed to fit battery packs.

You need a spot to charge your PHEV at home or you shouldn’t buy one at all. At first, it can feel annoying unplugging and plugging in (especially in the rain), though you soon get used to it.

The adaptive cruise control and lane centring in the latest cars are really good. It makes driving less taxing, though you still have to keep your wits about you as the systems still haven’t quite worked out merging just yet.

Thanks to Te Manatū Waka – Ministry of Transport

The Ministry engaged us to undertake this review and allowed us to unlock it for the benefit of all New Zealanders.

The vehicles were kindly loaned to us by Toyota, Ford, MG and Kia. The Hyundai Ioniq PHEV and Hybrid were loaned to us back in 2020.