By Vanessa Pratley

Investigative Journalist | Kaipūrongo Whakatewhatewha

After years of bad experiences with our mental health system, Maia* found herself trusting an AI chatbot.

Maia’s journey with depression has been a near-lifelong one. It began in her teens, and, now in her 60s, Maia has used mental health services countless times. She's stayed in psychiatric wards, worked with therapists and experienced many periods of distress.

Maia works in mental health herself, so she knows the system inside out. For a while, she went without interventions or medications, but last year, she became unwell again.

“I realised I was unwell, and I reached out for help. But the waiting list was really long. So, I rang Lifeline one night, and they freaked out and sent an ambulance and police to my home.”

Though she was in distress, Maia says it wasn’t an ambulance she needed but someone to talk to.

“After that, I rang 1737,” she tells me. 1737 is New Zealand’s free, confidential mental health helpline.

“I have used 1737 a lot in the past, but I got the ‘we're too busy to take any more calls right now’. And I was thinking, ‘Well, what am I going to do?’

“I didn't want to ring the crisis team, because I haven’t had a great experience with them in the past. And so, I just thought, why not try ChatGPT?”

Maia says the AI chatbot has been helpful.

“It's available when you need it; it never rejects you and it's free. I found it really validating and much more consistently empathetic than any of the other services I'd accessed over the years. I've been using services for a long time, and this was the best sort I'd ever experienced.”

Maia doesn’t have an account, but she’s found the free version of the technology works quite well for her.

“I just typed in what I was thinking, and it came back saying, ‘Sounds like you’re having a hard time. Sorry that you're feeling that way. Your life is important. Here are some suggestions that might help.’ And it talks, you know, talks me through things to do.”

The chatbot offered three or four strategies to help ease Maia’s mental distress. It asked Maia which suggestions she liked and disliked. And over time, it has come to know her preferences.

One of the best things, for Maia, is that the dialogue doesn’t feel condescending.

“Not once did I feel patronised or anything like that.”

Maia is quick to clarify the chatbot isn’t a replacement for traditional therapy.

“I don't see it as an either-or; I see it as a tool that, in addition to any other service you get, can provide more support,” she says.

I ask Maia if she trusts the chatbot, and she replies without hesitation.

“Yes. It’s never given me bad advice. I would say it saved my life.”

AI chatbots in a nutshell

Artificial intelligence (AI) generally refers to the ability of computer systems to do tasks that would historically require human intelligence. We can separate AI into two broad categories: discriminative and generative.

Most of us will have experienced discriminative AI. Email services use it to detect spam, and facial recognition systems use it to match photos to existing records. Any instance of categorising or sorting data probably involves discriminative AI.

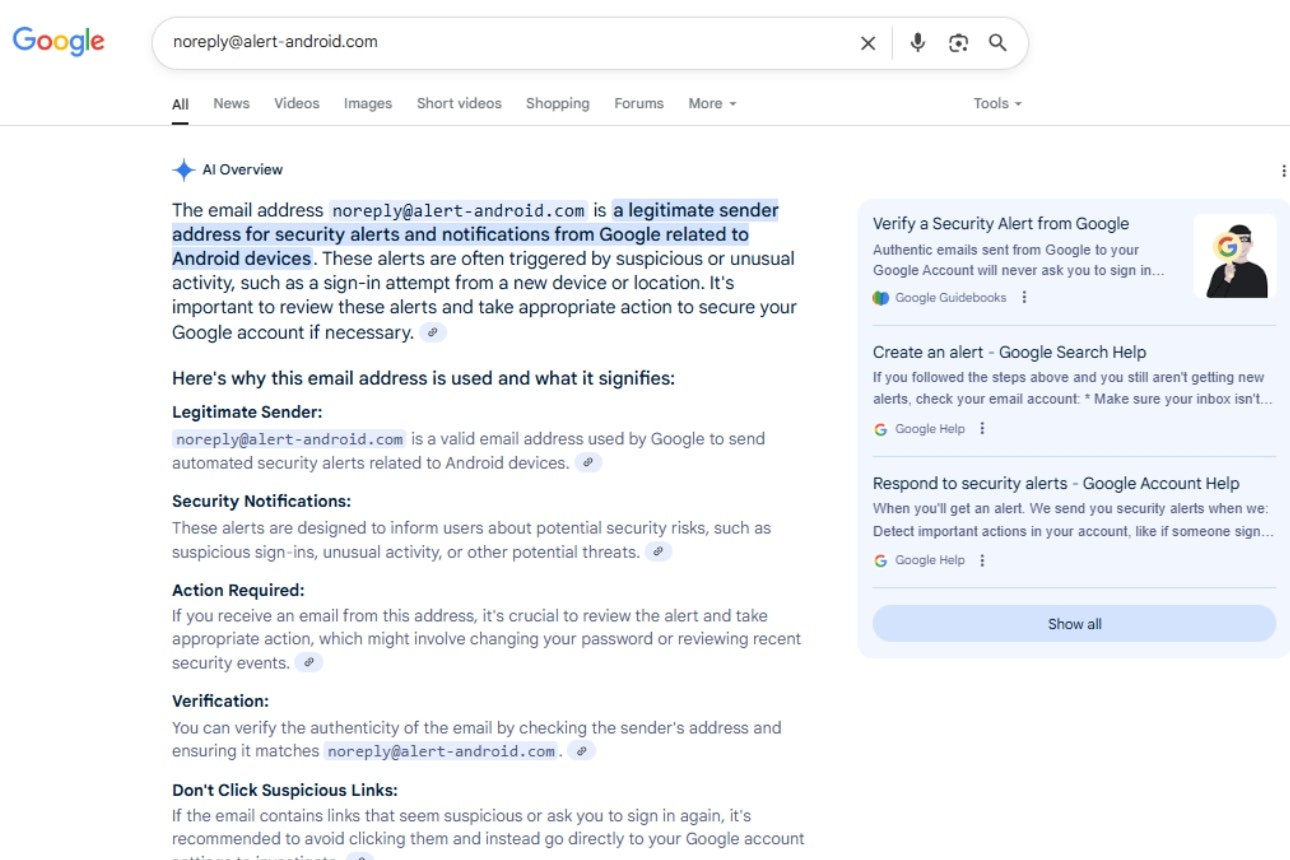

Generative AI has been around for a long time, but it has only become more common in public usage over the last decade. It involves creating new data. Popular examples include OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini. Users input a prompt, asking the model to answer a question, write text or problem-solve. It’s this form of AI we're discussing in this article.

Conversations with generative AI can flow like you’re texting a friend – it’s easy to see why AI could be an attractive option for someone looking for support.

AI mental health tools on the market

A recent trial of an AI chatbot found it could be an effective mental health tool. Dartmouth College in the United States developed the bot, called Therabot, in consultation with psychologists and psychiatrists. It was the first-ever clinical trial of a therapy chatbot.

According to the study, “Therabot users showed significantly greater reductions in symptoms of major depressive disorder” compared with the control group. However, the study’s first author, Michael Heinz, offers a note of caution, “While these results are very promising, no generative AI agent is ready to operate fully autonomously in mental health, where there is a wide range of high-risk scenarios it might encounter.”

But there are countless AI-enabled mental health chatbots available.

Ebb

Popular meditation and sleep app Headspace recently launched Ebb. Headspace describes Ebb as its “empathetic AI companion”.

Ebb is capable of giving personalised recommendations based on how you’re feeling. Headspace says mental health experts designed Ebb, and clinical psychologists had a hand in building and testing it. However, Headspace warns Ebb is no substitute for human care, does not provide clinical mental health services and is not monitored in real time by a human.

Youper

Youper is another app that “combines psychology and artificial intelligence to understand users’ emotional needs and engage in natural conversations”. Youper claims to be both safe and clinically validated and clinically effective at reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Wysa

Wysa describes its chatbot as an AI-powered wellbeing coach. It targets its services at employers, insurers and individuals. Its website claims 9 in 10 users find talking to the chatbot useful. It also claims it can reduce depression by 31%.

AI should be used with caution

Each of these services claims it was developed by or in consultation with healthcare professionals. ChatGPT, Gemini and other general AI models are different. They don’t claim to have any kind of clinical purpose or professional oversight.

Executive director of the New Zealand Psychological Society Veronica Pitt says, either way, AI should be used with caution.

“There may be some situations in which AI interventions offer a level of support, however they are not able to conduct nuanced assessment nor identify and respond to potential risk and safety concerns that are culturally appropriate and individually tailored to meet the needs of our diverse communities.”

She adds, “There are significant demands for mental health services in Aotearoa, with many psychologists having long waiting lists. Recent cuts across public services, particularly within Health New Zealand, have contributed to these wait times.”

You could also miss out on key rights as a healthcare consumer, because it isn’t clear if the usual rights apply to AI chatbots. Your rights are set out in the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights. Under the code, you’re entitled, among other rights, to:

be treated with respect

freedom from discrimination

dignity and independence

services of an appropriate standard provided with reasonable care and skill.

If an AI chatbot fails to uphold these rights, you might not have any course for redress.

What happens with AI and your privacy?

What happens to our data, particularly sensitive data, when we input it into a chatbot? Maia knows this question is important but says “when you're in that space, you don't really care about that kind of thing. You just want it to help.”

The answer depends on the service or chatbot you’re using, what its privacy policy says and whether you’ve got an account or subscription. If you are considering using an AI chatbot for anything, Privacy Commissioner Michael Webster says, “It’s important consumers understand and consider the privacy implications of the technology they are using.”

“Consumers may be surprised that data collection is happening via AI, so it’s important people know whether the purpose and scope of collection and sharing is clear. This is particularly important in the context of mental health chatbots where the information being shared with the chatbot is likely to contain health or other sensitive information,” Webster says.

“We encourage consumers to check what information will be collected and how it will be used before they engage chatbots, particularly mental health chatbots.”

Everyone in New Zealand using AI tools is covered by the Privacy Act 2020, even though those tools may be developed and owned overseas. If you think an organisation has breached the act and isn’t willing to help you sort out a satisfactory solution, you can complain to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner.

Unfortunately, privacy policies can be difficult to locate and understand. Our investigation into other apps that collect sensitive information, like period trackers, shows not many people understand how their data is being shared. We’d like to see more pressure placed on app providers to give clearer, more accessible information about how they use and sell data.

The risks and rewards of AI

Changing Minds is a not-for-profit run by and for people with a lived experience of mental distress, addiction or substance use. Its primary mission is to improve wellbeing.

Megan Elizabeth is Changing Minds’ engagement and insights manager. She says there’s one key concern with using AI chatbots as mental health tools.

“Are these tools being introduced as complimentary, or are they being proposed as a replacement for those person-centred, peer-to-peer relationships that our existing system is based on?”

According to Elizabeth, there’s a place for people to explore using AI tools as a complementary support, but as a replacement, AI could be a problem.

Elizabeth says there are issues with the current system. “We hear from people with a lot of different experiences within the system from around the country, and one thing we’re quite concerned about at the moment is that it is becoming harder for people to access the services and support they need.”

Changing Minds advocates for community-based supports and interventions. This model of care should be easy to access but is becoming increasingly difficult to get to, and Elizabeth says she understands why an AI chatbot is an attractive prospect.

“We hear from some members of our community who … understand what they need for maintaining their wellbeing – the types of therapy and support and interventions that work for them – that it’s beneficial to have AI at their fingertips, available whenever they're ready.”

But for others, it’s a different scenario, and Elizabeth says AI can’t replace what human connection does for our wellbeing.

Hallucinations are a risk, too. A hallucination is when AI confidently gives you the wrong answer or invents a source or fact. This phenomenon is common across most generative AI applications. But the consequences of hallucinations change based on the setting: it's funny when ChatGPT claims there are only two letter 'r's in the word 'strawberry'; it's dangerous when it can't give you the right phone number to call when you're in distress.

When I ask Elizabeth if AI is something we can trust with our mental health, she says there’s no right answer.

“It goes both ways for some people in our community. For those who have had really negative experiences trying to access support or counselling, if there is an alternative that allows them to engage in a conversation about their mental health in a space that feels secure to them, even if that is with an AI model, then I can see how that is a benefit.”

Where to get help

In an emergency, call 111.

Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor. 1737 is funded by Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand.

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 (0800 LIFELINE) or free text 4357 (HELP).

Youthline – 0800 376 633, free text 234 or email [email protected] or online chat.

*Name changed to protect privacy.

How to find a therapist

When you need extra support, counselling is one of the most effective treatments but it can be a challenge to access. Here’s our guide to help you navigate the system.