In the last three years, the number of electric vehicles (EVs) on our roads has increased more than tenfold – there are now over 10,000 registered. However, the uptake of electron-powered driving is hamstrung by a lack of affordable options; few battery-only EVs that’ll swallow a family; and range anxiety as most models can’t do much more than 200km on a full charge.

Though fully electric cars that smash these barriers are slowly becoming available, it’ll still be a few years until they’re a viable option for most consumers. An alternative for families looking for an electric-powered alternative today is a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV). I trialled two family-friendly PHEVs: the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV and the Mini Cooper S Countryman E All4.

The Outlander, available since 2013, is New Zealand’s best-selling PHEV. A new VRX model costs $55,990, just $1000 more than the petrol-powered version. Five-year-old used imports can be scored for half that price. The Countryman E was released in May last year and sells new for $59,900 ($3000 more than the petrol equivalent). As it’s a relatively recent model, you won’t find many on the used car market.

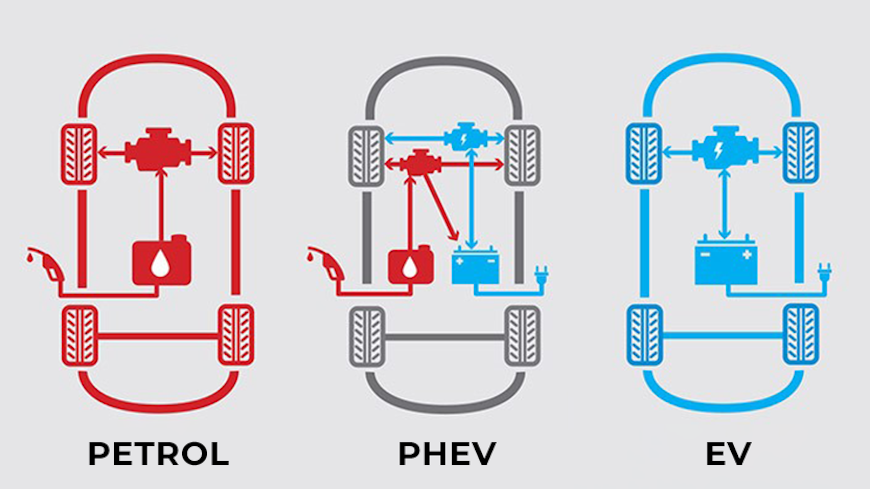

PHEVs have an electric motor and a conventional petrol engine. The car uses its electric motor for up to about 40km, with the petrol engine kicking in to extend its range to that of a conventional car. Including a petrol engine means, unlike battery-only EVs, PHEVs don’t need to be small cars and there’s no range anxiety — if the battery runs out, petrol keeps you moving.

Electric-powered range

PHEVs don’t have as many batteries as electric-only EVs, so they can’t travel as far using electric power. Mitsubishi claims the Outlander PHEV will cover 54km, while Mini claims “up to 40km” for the Countryman E.

I didn’t get close to these distances during my trial. In hilly Wellington, the best electric-only range I managed was 30km in the Mini and 37km in the Outlander. Making two 12km round trips from my home, 200m above sea level, to the CBD (at sea level) drained the batteries of both cars. This isn’t surprising as they’re medium-sized SUVs, made heavier by carrying both petrol and electric drives – lugging all that weight kills electric range.

Fuel efficiency

Manufacturers make fantastic fuel efficiency claims for their PHEVs. On the “combined cycle” test the Outlander manages 1.7L and the Mini 2.3L per 100km. The combined cycle is a lab test using a rolling road. It combines an urban cycle, which simulates driving in traffic, and an extra-urban cycle, which simulates open road conditions. In total, the test runs for 20 minutes.

It’s unlikely you’ll be doing much of your driving in a lab so, while you could see this performance on short trips, your real-world mix of urban and open road driving will be much less efficient.

Short trips are when petrol consumption skyrockets and petrol engines take a beating. Stop-start travel, especially when the engine is cold, pumps out more emissions too. So everyday local trips are ideal for electric drive. If you keep within the limited electric range of these PHEVs and drive with efficiency in mind, you’ll use little or no petrol and emit only rainbows and unicorns.

If you drive a PHEV further than about 30km, you’ll start burning petrol and get similar fuel efficiency to that of a conventional car.

After a few weeks of urban driving, covering 150km in the Mini and 265km in the Outlander, neither PHEV used more than a couple of litres of petrol – not enough to register on the fuel gauge. My driving experience suggested the Mini was less efficient, as I noticed it making more use of its petrol engine to assist its lower-power electric motor. It’s also more performance-oriented than the Outlander (and much more fun to drive). I topped up the batteries at home each night. My power bill increased by a little over $5 for the 36kW I fed into the Mini and just less than $10 for the 62kW that refilled the Outlander’s cells.

The Mini Cooper S Countryman E All4.

PHEVs use a regenerative braking system, just like fully electric EVs, to recover energy and charge the battery. They also have a neat trick for open-road driving. By using the petrol engine to charge the battery when cruising efficiently, they can switch to electric drive when pushed harder – such as on twisty, hilly roads. It doesn’t make a mind-blowing difference, but it delivers a small net gain.

On a trip from Auckland to Wellington, driven with scant regard for efficiency, the Mini managed 6.7L/100km. On a return trip between Wellington and Hawke’s Bay, the Outlander used 6.3L/100km. Batteries in both were fully charged when starting out. While it’s not bad for medium-sized SUVs, it’s not that much better than what I’d expect from a modern petrol-powered car.

Trial by journey

The Mini covered a trip between Auckland and Wellington (petrol-powered), 150km of short local trips (recharged each night) and a 95km regional journey (using both electric and petrol power). Over the trial it averaged 6.4L/100km – not bad for a car meant to be driven hard.

The Outlander journeys included a return trip from Wellington to Hawke’s Bay (petrol-powered), 265km of short local trips (recharged each night) and a 120km regional route (using both electric and petrol power). The less performance-inclined Outlander PHEV averaged a frugal 5.3L/100km.

Mini: 890km total, 150km local, 95km regional, 645km highway

– 6.6L/100km

Outlander: 890km, 265km local, 120km regional, 505km highway

– 5.3L/100km

Under the hood

The Countryman E and Outlander PHEV use a petrol engine and electric motors. They also have all-wheel-drive (AWD) systems. But that’s where similarities end.

The Outlander uses 60kW electric motors on each axle to drive the wheels most of the time. Its 2.0L, 88kW petrol engine is primarily used to power the electric motors and charge the battery. However, when maximum power is called for, or when the car is cruising efficiently, the petrol-engine drives the front wheels.

The Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV.

The rear wheels of the Countryman are driven by a 65kW electric motor. It has a 100kW 1.5L turbocharged petrol engine that powers the front wheels and can also charge the battery. When both petrol engine and electric motor are used, all four wheels are driven. While the Mini can run electric-only, the less-powerful electric motor usually works with the petrol engine (floor the accelerator to get an electric “boost”).

When you start up a PHEV, the standard mode has the car deciding when to drive electric and when to use petrol-power. You never need to know what’s powering your wheels. If you want more control, you can force the car to use only electric drive until the battery is near-exhausted (though the petrol engine will kick in if needed). During my trials, I frequently chose the electric-only mode for short trips. Total control-freaks can manually force the petrol engine to charge the battery, but it’s usually more efficient to let the computing power in the car make that decision for you.

Just like a real car

To fit batteries into these cars, a few compromises have been made when compared to the petrol-only versions. Both PHEVs have less boot space and smaller fuel tanks. The Outlander PHEV comes with a tyre repair kit instead of the full-sized spare wheel included in the petrol version (all versions of the Mini Countryman have run-flat tyres).

Otherwise, the PHEV versions of these cars are equivalent to their petrol-powered siblings. They come with high levels of safety equipment, the latest driver aids and comprehensive infotainment systems. They are both sized to accommodate a small family and, unlike fully electric EVs, are rated for towing.

Reliability

PHEVs could be seen as offering the best of both electric and conventionally fuelled cars, or as being excessively complicated while being neither one nor the other. A potential downside of their complexity is reliability – or lack of it. However, results from our latest reliability survey suggest they are a little more reliable than petrol cars of a similar age, perhaps because the trouble-causing combustion engine isn’t used as much in a PHEV.

In our survey of 35 PHEV owners, 83% said their vehicles were trouble-free, 100% were very satisfied with fuel economy, and 93% would recommend.

To PHEV or not to PHEV?

PHEVs could be the ideal solution for people who want to go electric now, but need a larger car and longer range – people like me. Though they have only limited electric range, they use that electric power where it matters most – on short local trips. It’s only a matter of time before family-friendly full EVs become a viable option, but a PHEV could fill the gap for the next few years.

Before this trial, I was sold on a fully electric car, but put off by the price and lack of suitable-sized options for my one-car family. But after experiencing a PHEV, and realising how much of my daily use is covered by the 30km electric range, a nearly new PHEV appeals – especially after factoring in the fuel saving to offset the upfront cost. Then, perhaps in a few years, there’ll be a battery-only EV suitable for my family and the PHEV can be sold on to someone looking for an easy way into driving electric.

By Paul Smith

Head of Testing