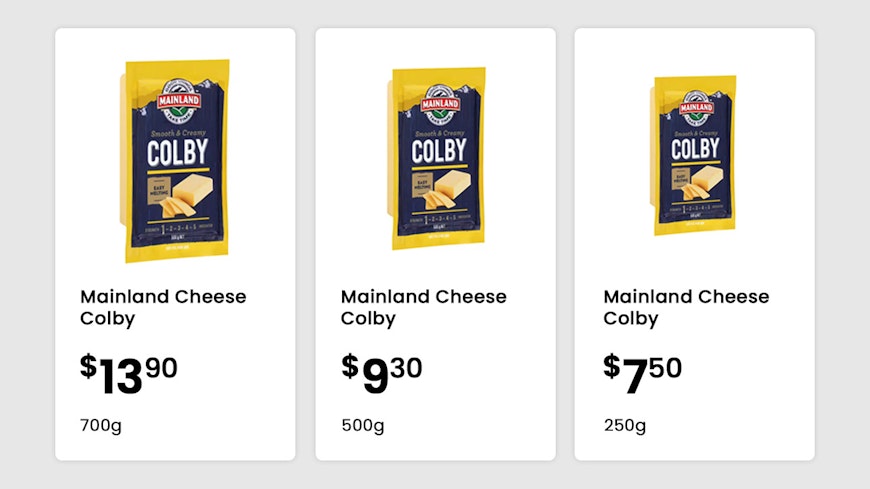

Picture this. You’re standing beside the supermarket chiller trying to work out which size block of Mainland Colby cheese to buy.

For most of us, working out which block is the best value requires some tricky head maths that we simply don’t have time for at the supermarket.

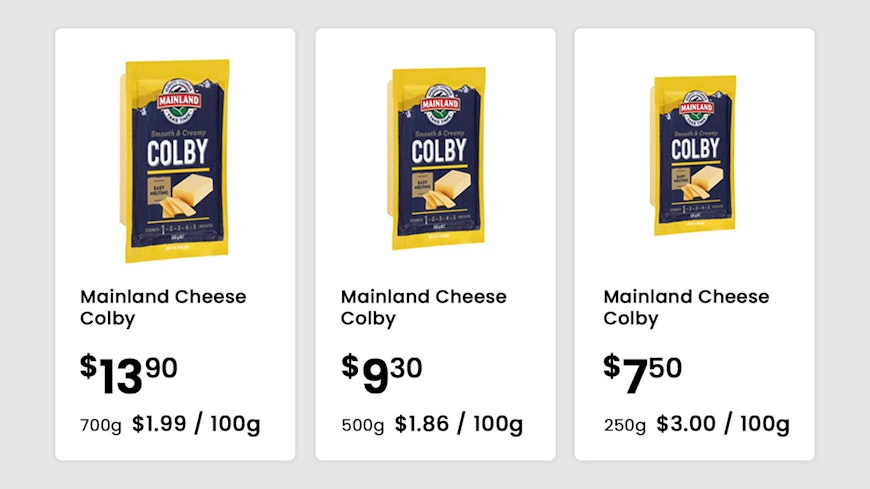

Enter unit pricing – it’s when we can see the cost per unit. For example, how much we’re paying per 100g or 100ml.

In the case of the cheese, unit pricing lets us see how much we’re paying per 100g. And suddenly, it’s easy to see the 500g block is the best value, as it’s the cheapest per 100g.

How else can we use unit pricing to save money?

To compare different types of products

Let’s keep rolling with the cheese scenario. Maybe you spot the grated cheese out the corner of your eye and wonder how much more you’ll be paying for the convenience.

The different product sizes (500g vs 400g) make it tricky to compare prices until you check out the unit pricing. The grated is more expensive and knowing that lets you decide if you’re willing to pay the difference.

To work out if a “special” is worth buying

What if the 250g block has a big “special” tag on it, showing that the price has come down from $7.50 to $5.90? Should you now buy it instead of the 500g?

The unit price says no – despite the allure of the special tag, the 500g is still the best value buy.

To compare brands

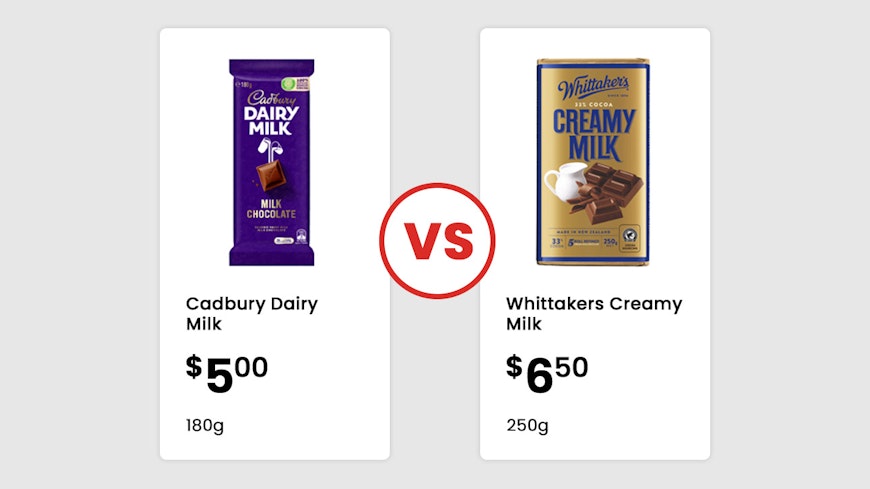

We’re going to abandon the cheese examples at this point and move onto chocolate – a product that comes in irregular size packets, making it hard to compare the cost.

Without knowing the unit price, which of these would you think is the best buy?

It’s only with our friend unit pricing we can see the Whittakers would be the best buy at $2.60/100g versus the Cadbury at $2.78/100g.

What are the unit pricing rules?

From 31 August 2023, unit pricing regulations made under the Fair Trading Act came into force. They make unit pricing mandatory but supermarkets have a year’s grace period before they must comply with the regulations. They get another year – until 31 August 2025 – before their websites must display unit pricing too.

We’re glad there’s progress, but frustrated it’s still taking so long for consumers to be able tell at a glance what the best value choice is – especially during a cost-of-living crisis.

Smaller stores, under 1000sqm, don’t have to display unit pricing – but if they choose to, they’ll have to stick to the unit pricing rules.

There’s a list of measurements stores must use based on the type of product. For example, meat must be priced per kilogram, drinks per litre and toilet paper per 100 sheets.

Some products are exempt from having to display unit pricing, such as alcohol, tobacco, magazines, flowers and toys.

The unit price also has to be shown “clearly and legibly”. The font size of the unit price must be at least 25% of the font size of the price. It must also be displayed close to the price.

We can't do this without you.

Consumer NZ is independent and not-for-profit. We depend on the generous support of our members and donors to keep us fighting for a better deal for all New Zealanders. Donate today to support our work.